Women against the grain

Women in Cambodia, India, Kenya and Indonesia share how they are on the frontlines in the resistance against powerful sand mining operations in their communities.

In a trade that is dominated and driven by men, women often bear the burden of the negative social and environmental impacts from sand mining activities across the world. This is evident in much of our reporting on the global industry. As is common with many environmental issues we face today, we feel that the disproportionate burden to women is a heavily underreported issue.

Across our reporting, women are depicted as front runners in protests against large-scale — and often, illicit — mining operations. As farmers, mothers, family care-givers, fishers, landowners and more, the women we met and interviewed are acutely aware of how the sand mining industry can hinder their community lands and livelihoods.

In this series, the Environmental Reporting Collective highlights examples from Cambodia, India, Kenya and Indonesia in which mining projects have hindered women’s rights, resulting in increased gender inequality and the further marginalization and abuse of women. We also share stories of women on the frontlines of sand mining, showcasing how they are playing an active role in the resistance against mining activities.

Our hope in sharing these lived experiences is to contribute to a broader perspective on environmental justice.

Cambodia

The Wooden House

This comic has been illustrated based on interviews with Sok Lang and her family and six other residents of Ta Ek commune in December 2022.

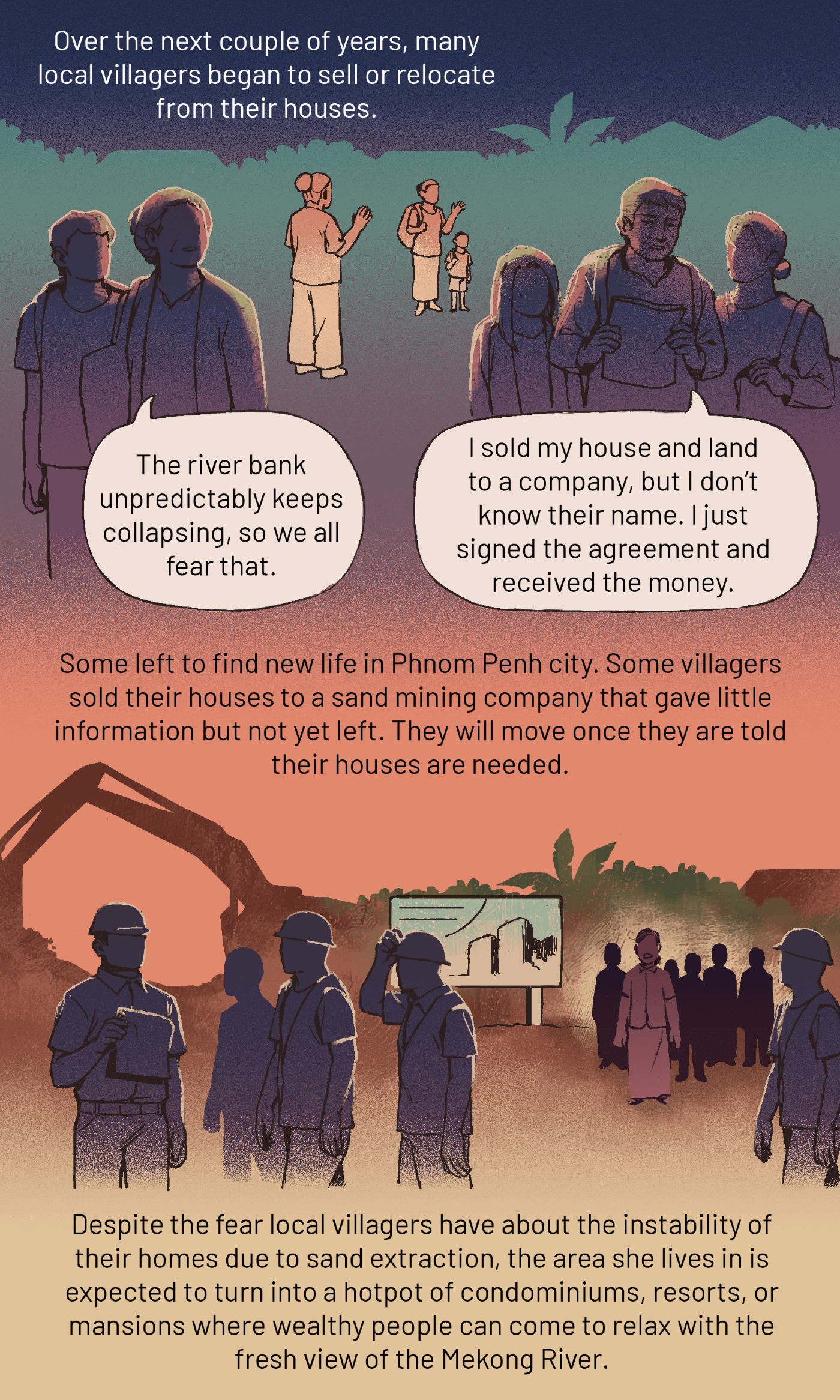

Sor Sok Lang, a resident of Ta Ek commune in Kandal Province, 40 kilometers from Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh, has often thought about leaving her house. It is located on the banks of the Mekong River, which has been eating away at Sok Lang’s land each year. Back in 2011, nearly a third of the wooden houses in Ta Ek were lost to a riverbank collapse. Both Sok Lang’s house and grocery business were completely gone in another incident five years later.

She rebuilt her home for her family of five with corrugated metal sheets. But she says that life since has been full of uncertainty.

The Environmental Reporting Collective visited Ta Ek commune and interviewed six residents in December 2022, as part of a global series on how sand mining has disproportionately impacted women.

“When there was a strong wind, I started to feel frustrated due to the fear of the house collapsing,” said Sok Lang. “Who would not get scared?”

Residents in her co to mmunity believe the series of riverbank collapses is linked to rampant sand mining, which scoops up the sand from the river and destabilizes the riverbank.

Kandal Province is one of Cambodia’s most popular extraction sites for river sand. Though dredging is allowed from 6 am to 6 pm, Sok Lang can hear the roar of machines through the night. The ships rarely stop carrying the sand from the sites to unknown destinations.

She believes this sand will be soon used for construction in her community area too, where developers are eyeing the panoramic view along the Mekong River as a prime site for future luxury condominiums and resorts.

In the past decade, Cambodia’s hunger for sand has been intensified by its pursuit of economic prosperity. Urbanization and infrastructure, especially road networks, have been rapidly expanded.

The country’s construction sector is projected to grow 9.4% between 2023 and 2026 due to ongoing investments in infrastructure, commercial and residential buildings, and the strong demand for real estate.

A recent study led by Christopher Hackney, a research fellow at the School of Geography, Politics and Sociology at Newcastle University, found that the volume of river sand extraction in Cambodia has doubled since the early 2010s.

Hackney’s research team used monthly high-resolution satellite imagery to track sand barges and to estimate volumes of sand extraction throughout the Mekong River in Cambodia. It shows the increasing rate of sand extraction from 24 million tons in 2016 to 59 million tons in 2020.

The loss of sand can cause disasters in many ways, he said, including riverbank erosion, the devastation of animal habitats and fish breeding grounds, and sediment loss in downstream countries.

Riverbank erosion has been reported across Cambodia, as well as in Thailand and Vietnam. This negatively affects women’s and girls’ lives in different ways, including through the loss of educational opportunities.

After Sor Sok Langlost her house and grocery business to the riverbank collapse, her 44-year-old husband Tong Peng Karng became the breadwinner of the family and barely earned enough to feed them all.

The family has been in debt after the incident and must pay a monthly repayment of US$300 to their bank; they are struggling to pay the school fees for their three daughters.

The eldest daughter, Karng Ghek Mouy, 20, must end her dream of pursuing a law degree. She will soon move to Phnom Penh City to work as a cashier in a newly opened mart.

The other two daughters, in grades 9 and 11, are not sure if they can obtain university degrees due to their parent’s financial constraints.

“We don’t know what the future will hold for our family. But for now, we only want the safety of all our family members,” said Sor Sok Lang, while preparing her plan to leave the Mekong River.

India

The Mothers of Morhar

This comic has been illustrated based on interviews with the six arrested women and several other residents of Arhatpur in December 2022. Visuals of handcuffing and arrest from February 2022 have also been referenced.

The police say that they used force in response as they were attacked and injured by the villagers, who were opposed to sand mining.

On February 15, 2022, when the district administration and police arrived to demarcate a sand mine on Morhar river in Arhatpur village, protesting locals were met by police firing tear gas.

Several men and women were beaten up, and among the 10 people eventually arrested were five women and a minor girl. The police handcuffed the women with pieces of their own clothing. They also beat up a disabled woman in her fifties, but did not arrest her.

The police claim that they used force because the residents were attacking the officials.

As part of a global report on sand mining by the Environmental Reporting Collective, journalists Shamsheer Yousaf and Monica Jha visited Arhatpur in December 2022 and interviewed the five women and minor girl who were arrested and spent 37 days in jail. They spoke about their arrest and their opposition to sand mining, and about the challenges of getting out on bail.

Rampant and often illegal, sand mining has ruined several rivers in Bihar, an eastern state of India. The activity has destroyed agricultural lands, washed away homes, and killed people. Women bear a disproportionate burden of this impact.

In Bihar, legal mining by private companies was banned following a court order issued in 2020. The demarcation in Arhatpur village was in preparation for a fresh auction toissue new leases, but the auction has not yet been concluded. Still, residents claim that illegal mining by a sand mafia is thriving in the Morhar river.

Their opposition stems from fear. The government is creating a new ghat (mine) where none existed in the past. The women farmers fear that sand mining will affect the availability of groundwater, submerge their farm lands, and reduce crop production. It will eventually change the course of the river and flood the village. The dredging of sand would also create dangerous pits in the river where their children and cattle could drown.

It doesn’t help that the miners are upper caste Bhumihars from a neighboring village and that Arhatpur is dominated by Yadavs, who sit in the middle of the caste hierarchy and are categorized by the government as an ‘Other Backward Caste’.

Sand miners aren’t here just to make money, said Geeta Devi, one of the six arrested women. “They are here to finish us.”

Sand mining has ruined the lives of women in other ways. While the women of Arhatpur are up against the system, on the banks of the Sone river in central Bihar, several mothers mourn the loss of their young sons who were killed while working in sand mines.

The victims, who are daily wage workers, come from disadvantaged castes and are often landless. For them, working as a daily wage labourer in sand mining is the only work available.

But these jobs are incredibly dangerous. At least 76 people lost their lives and 103 were injured in sand mining related accidents and violence between December 2020 and March 2022 in Bihar, according to a report from the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People.

Several workers also die every year when sand-laden boats capsize or when masses of sand collapse on labourers working in sand pits.

Radhika Devi, a resident of Semaria village on the bank of Sone river, wondered if her son would have survived if he didn’t return home when his school shut during the Covid-19 pandemic. “He was studying to get a good job and support us in our old age,” she said. “But that was not to be.”

The illegal sand industry has left the region full of unsupported parents. But the irony is that many young men work in the sand business to provide for their parents.

Take the case of Kanti Devi. In August 2022, she lost her 23 year old son, Rajan Paswan, in a cooking gas explosion aboard a sand laden boat. He was a Mahadalit, the state government’s term to refer to the most marginalized among the oppressed castes.

And yet, Kanti Devi’s younger son, Anand, continues to work in sand mining. He says this is the only job available here.

“How am I going to look after my old parents? I have to work in the mines to support them,” he said, adding, “Even if it means I might die doing it.”

Kenya

The Harvesting Site

This comic has been illustrated based on interviews with residents from two rural villages across Homa Bay in western Kenya during December 2022 and February 2023.

The sand mining site neighboring where Mary Atieno lived was mined to exhaustion. After years of constant activity, the land was dredged so heavily that the sand lorries no longer had enough space to enter the site.

Despite this, it was not unsurprising when Atieno’s nephew Geoffrey and his friend, both young boys aged 12, asked if they could work on the site.

Although Kenyan law prohibits the employment of minors, it is usually school-going boys who tend to work on sand mining sites during evening hours, in exchange for a small income.

The work involves scooping sand or loading trucks for as much as shs.100-200 per day ($1-$2 USD) depending on the amount of work done.

Dangerous working conditions and a lack of protective equipment on the private lands where sand mining activities take place often lead to casualties and injuries.

The evening that Atieno’s nephew and friend were buried under the sand, it took rescuers over 10 hours to find their bodies.

The owner of the mine continued operations, despite the deaths of the two children and injuries of several others. The boys were taken to a mortuary and buried in graves, but no action was taken against the landowner.

“I was so sad for them,” said Atieno. “They had their whole lives ahead of them.”

As part of a global report conducted by the Environmental Reporting Collective, journalists visited two rural villages across Kobala County in eastern Kenya, where sand mining activities run unmonitored, and accidents are rife.

Atieno’s nephew Geoffrey would visit often and help her maintain and cultivate her land. With his loss, she faces a higher physical burden. By being so close to the mining site, Atieno also faces a greater risk of her house collapsing from the erosion occurring at the abandoned harvesting site left by her neighbor.

Already, the small strip of land separating her house and the abandoned site is showing signs of weakness, with cracks all over the ground.

“In the coming year, we will not be standing here. This place will have turned into a river,” says Atieno.

The incident at Rakwaro village is one of many cases reported in sand-mining villages across Kenya. In 2022, five students died in Kobuya, another village in western Kenya, when sand mines collapsed on them in three separate incidents. Damianus Osano, the area chief, referred to the activity as a “death trap”.

However, the total number of deaths from sand mining cannot be properly accounted for as there is no proper documentation available. Tens of people die each year in these villages in similar incidents, according to reports by residents.

Nearly 200 meters away from Atieno is Imelda Auma, 52, a mother of two and a former sand miner living in Kobala village. She almost lost her three-year-old daughter when sand fell on her at a harvesting site.

One particular morning, her child had followed Auma to the site where she used to work as a casual laborer, scooping sand to make ends meet. As Auma bent down at the site, the baby came from behind and fell into the pit without her knowledge.

“Suddenly, I heard a sound, and then I lifted my head and saw volumes of sand avalanching down but I had not checked the pit to confirm if there was anybody,” she said.

“A second heap which was very huge also fell. The pit was so deep that when the heap fell, it covered her completely until it became level.”

It took two hours for her daughter to be uncovered out of the sand rubble. She was found lying on her belly. One month of medication was needed to relieve her from the chest pains she experienced after the accident.

Had it not been for the quick intervention and skillfulness of the rescuers, Auma believes that her baby would have died.

But some are not as lucky.

In 2019, the Director General of the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA), Josiah Nyandoro, imposed a ban on illegal sand harvesting in several villages across western Kenya, including in Rakwaro and Kobuya.

All sites must now be subject to environmental impact assessments in order to obtain a legal license.

According to Nyandoro, the impact assessments should be followed by serious and adequate public participation so that the communities can share their thoughts, paving the way for mitigation measures that are considered homegrown.

However, only one company, Mango Tree, has been licensed to carry out sand harvesting in Homa Bay county. The rest are illegal, declares Nyandoro.

For the last three years, NEMA has arrested 69 people for mining without a license, who have been fined between Kshs. 5,000 - 200,000 ($50 -200 USD).

Beyond the risks to worker safety are the extensive environmental and social costs to the areas surrounding the sand mining site.

Unmonitored mining activities have caused Atieno a lot of pain. With the impact she faces on her land from the abandoned site, she is now calling on the government to take action and reclaim the land before it erodes any further.

"Sand harvesting hurts the community. When somebody dies, you cannot say it is not harmful. When it kills a person, it sends a resounding message that sand harvesting should not be carried out on farms," Atieno said.

Indonesia

The Remis Shields

This comic has been illustrated based on interviews with the women in Pasar Seluma in December 2022.

For over four generations, the indigenous Serawai community in Pasar Seluma has been making a living from beremis, the traditional practice of collecting saltwater mussels (‘remis’).

Based in the coastal and iron-rich part of Bengkulu, Indonesia, the mostly women-led trade has been a vital source of protein and income for families.

However, the women of the Serawai community are now fighting to protect their coastlines from a powerful iron sand mining company that recently acquired a permit to mine near the remis harvesting grounds.

The ERC visited Pasar Seluma in December 2022 during the latest women-led protests against mining activity.

“There is so much to worry about. Our livelihood would be lost, [what about] our children, our fishing. If mining operates, what would it be?” asked Resda, 58, a Serawai woman who has been protesting against the company for more than a decade.

It began 50 years ago when it was discovered that the village was rich in iron sand. When samples were taken by researchers, the community began to sound an alarm. The elders gathered and warned the villagers to protect the trees, beaches and sands, as well as the remis habitats.

Pasar Seluma village is located on the west coast of Bengkulu, and is now known for its iron sands and abundance of mussels. However, the land has suffered a catastrophic environmental disaster after PT Agri Andalas, a giant palm oil company, stripped the local rainforest, occupying the customary land of the Serawai since 1991. Any new iron sand mining expansion is believed to further jeopardize the ecology impact.

For over a decade, two companies have been attempting to exploit the coast, which has become a collective communal site for the Serawai and other tribes in the nearby villages. Firstly in 2010, PT Famiaterdio Nagara, which occupied an area close to the Pasar Seluma village, illegally mined the iron sands. The company hadobtained a permit only for a loading zone for its sand mine not far from the nearby village. The illicit activities have caused controversy among the residents, many of them denouncing the company.

The conflict reached a peak in 2010, when over 100 men from the village protested and torched the company excavators. As a result, police searched the village in an attempt to arrest the men,who were hiding in the mosque.

In a defiant act, the women of the village, roughly 50 of them, surrounded the mosque to block the police officers from entering. For over five hours they stood shoulder-to-shoulder, before the village elders came to negotiate with the officers.

When the police called out to the men inside the mosque and provoked them to leave the building, the women replied, “They are not your opponents, we are,” recalled Zemi Sipantri, 35, a Serawai woman who had formed part of the shield.

The police agreed to withdraw from the village after the men conceded to surrender the next day.

During the conflict, another sand mining company, PT Faminglevto Baktiabadi received a permit to mine the coastal area in the Serawai collective communal site. This had happened without the acknowledgement of the head of the village and the residents, However, the company had to temporarily halt operations after the mosque incident in the village.

Faminglevto only came back a decade later, building the site and starting to place the excavators in 2020. By 2021, the villagers had decided to protest yet again, but this time they were led by the women. Dozens of women and children set up a tent within the mining site to demand that the company stop operations.

The remis became the main symbol of their campaign, as they advocated for their habitats to not be threatened by mining operations. The women were seen as shields for their community.

The police began to use excessive force on the women and the children and coerced them into leaving the tent. Eventually, two women were arrested and interrogated by the police.

When approached for comment regarding the use of excessive force, the head of police in Pasar Seluma refused to provide a response.

“There was sadness and there was happiness,” said Fitri Handayani, 32, who was among the two women arrested and interrogated by police. “What's sad is that we were innocent. Why couldn’t they treat us properly? But what made me happy was when all my friends hugged each other. We were united. The women also visited us at the police station. It didn't break our spirit, and made it grow more.”

After the arrest of the women, PT Famiaterdio Nagara temporarily halted its operations for one year.

By 2022, the company reopened its iron mining sites, prompting more protests from the women. While Flaminglevto has begun digging for iron sand in the area, the company has not officially transported any sand made any official transports.

ERC has contacted the company, but did not receive a response before the publication date.

The women say they are constantly evolving their strategy for peaceful protest. They are communicating with human rights organizations, and have even taken a course on how to organize advocacy campaigns.

In the meantime, the women continue to practice beremis, which is the symbol of their movement.

“Our hope, now and then, we don't want any mining. Because even without mining, we already have a prosperous, glorious, and thriving life.” said Resda.